All vendors are at risk of failure. How are you preparing?Gartner recently published its “2023 Top Legal and Compliance Technology Predictions,” where it predicted that 25% of existing legal tech providers will no longer exist by 2026. Gartner suggests more thorough vendor management programs as well as ensuring you have a means for retrieving your data should a vendor in your stack exit unexpectedly.

Background Knowledge

According to the US Small Business Association, about 20% of all new businesses fail in their first year, and about 30% fail in the second year. This actuality is that this risk affects all businesses using all types of vendors. Simple math tells us that -- depending on your mix of vendors -- you should assume that 10-30% of your vendors will be gone in the next 18 months. Worse yet, the failure rates only get higher as vendors mature with 50% of all business failing in the first five years.

This is a reality facing many vendors you work with. While it’s easier to conduct diligence on large, existing companies, it’s incredibly difficult to accurately assess risk of new and unproven vendors. We suggest adopting simple but objectives standards to score and manage vendor risk around the cash position of tech companies with less than a decade in business.

Some Discussion

Please tell me you’re already doing something to manage this perpetual risk.

Let’s assume that you already have some type of vendor risk management program in place where someone on your team is responsible for conducting regular, updated diligence on your universe of vendors. Maybe they do diligence on every vendor every year or maybe the risk team aligns updating diligence to contract renewal. There is not perfect answer or protocol, so as long as you’re doing it, you’re doing it right.

But, times are a bit unpredictable, perhaps “volatile” as the Gartner white paper suggests. It’s true that VC and PE funding is down. But, the only way that has any impact on you as a buyer is if your vendor needs money to continue serving you. If your vendor has money in the bank and is able to provide you business-as-usual services, why should you care if VC money isn’t flowing in like gangbusters?

So, the way to mitigate the risk of vendor failure is to figure out how much money they have in the bank. Public companies are easy – listen to or read their annual report. For established vendors who are privately held, consider formalizing a review process similar (or exactly the same) as you put vendors through when you first sign them up. These more established and mature vendors have more to lose, and thus are less likely, to misrepresent their situation in writing. Remember, you’re conducting due diligence, not an investigation. You’ll never perfectly understand every element of risk. Whether or not you can establish a known risk now, having the vendor establish what they do or don’t do in writing can be of tremendous value if things go bad.

How Does the State of the VC or PE Market Impact You?

The VC and PE climate is especially bad for companies with existing, potentially inflated valuations. For instance, it might be difficult for a 6-year-old company who’s been valued as a unicorn (a $1B valuation) to get new money at that same billion-dollar valuation. That means that if they’re not generating enough revenue to cover expenses, they have two major sets of options: either accept new money at a lower valuation potentially sending negative signals to the market or stretch their existing money as long as possible to wait for a better funding environment. Waiting for a better valuation often leads to cutting expenses, service reductions, and layoffs. All of which could impact your business in a major way.

For startups and vendors who have less than 10 years in business, I suggest doing some of your own diligence as a sense check to the data they provide during your review. Here’s one way that you might try to put some objective analysis around the black box that many young companies represent.

Factor #1. Look at the talent. Has leadership been turning over? Are they laying people off? Neither necessarily means anything is wrong, but key people leaving is always a concern. Ask the question. In writing, “Why did Sam leave?” And then consider the answer. Is it logical? Do they people who remain have the skills and talent to carry the company forward? Does anything seem off? Do you get the impression that they’re struggling internally? That can be an indication of dwindling money in the bank and the stress that comes along with that.

Factor #2. Try to determine when the company last had an injection of cash. You can find this data for most US and some international transactions in CrunchBase via a free plan, though any news source you find reliable will suffice. If they’ve received a notable funding round in the past 6 months, they should have to have money to make it at least 12 more months. Let’s say a company’s last funding round was in January 2022. I’d consider that worthy of a deeper dive because they haven’t publicly taken on new funding in the past 18 months. I’d worry that they’re running low on operating capital.

Factor #3. Can you surmise the “T-shirt size” of their likely revenue? If you’re not familiar with the “T-shirt size” analogy, it’s a rough sizing methodology used in product development (is it a Small, Medium, or Large?). How many customers do you believe they have? Can you find announcements where they’ve brought on large companies? Do you know anyone else who has a contract with the vendor? Do you believe they’re earning a small, medium, or large amount of revenue? If they have a probable “large” revenue stream, maybe they no longer need outside funding. If you suspect revenues remain small, however, the last funding round becomes more relevant.

Factor #4. Can you figure out how much money they’re spending on a monthly basis? There’s a couple of ways to roughly estimate based on publicly available information. First, give it a t-shirt size. Are they the primary sponsor at every event large and small? It’s hard to get a small sponsorship for less than $10,000 and a vendor couple easily get into the hundreds of thousands or millions of spending per year on events. I’d suggest that’s a company spending money on the “large” scale who might burning (or spending) money quickly.

An alternate means of calculating monthly burn rates is by making some standard assumptions about money in and out. If we assume that companies don’t ask for new money until they really need it (since it dilutes the founders’ interest), we can roughly guess that a company has $0 available when they take on new funding. If you divide the total amount of funding received by the number of months in business, you can get a feel for their spending (small, medium, or large). For example, if a company has taken in $300 million over their 100 months in business, I roughly assume they’ve been spending about $3 million per month. I’d call that a “large” amount of spending.

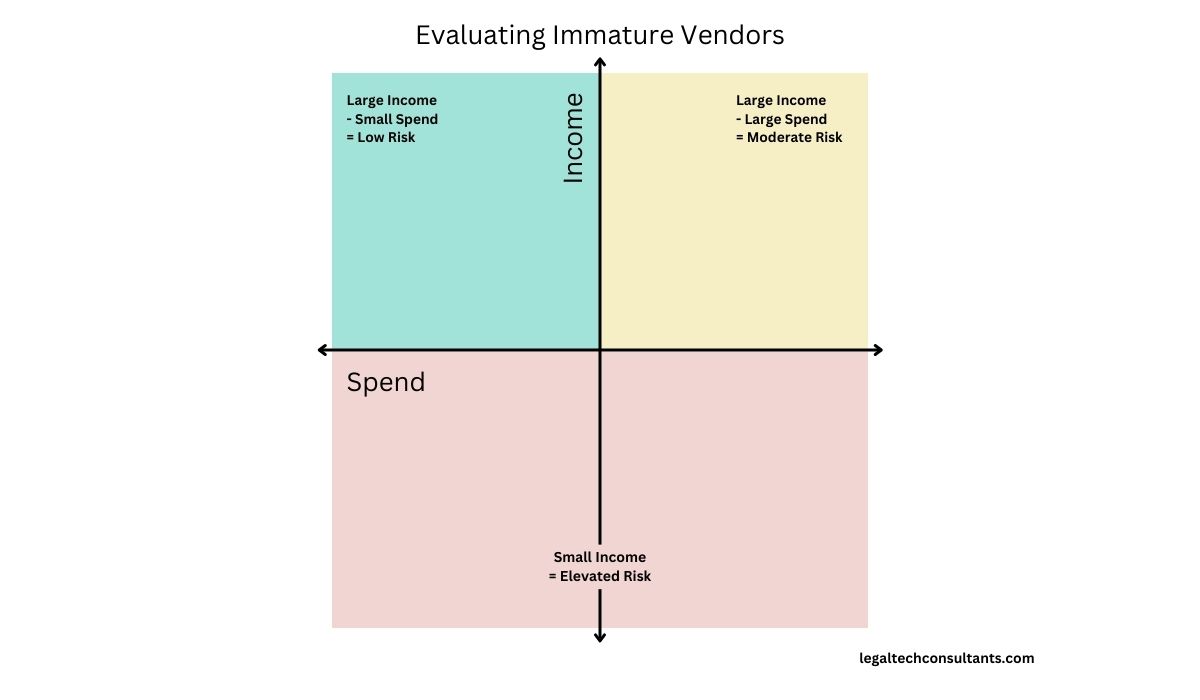

Factor #5. Do the math. Subtract the monthly spending from the likely revenue. If you expect a vendor is bringing in a large amount of revenue and a small or medium amount of monthly spending, they’re probably lower risk from a financial longevity standpoint. If you’re assuming they’re attracting a small amount of revenue and they haven’t been funded in the last 6 months, score this as an elevated risk for review. Take some time to decide how high impact this vendor’s failure would be on your company. If it’s a big risk, put a mitigation plan in place. This could be as easy set increasing backups or as complex as switching vendors.

Though there's no way to be sure that a vendor will survive your next contract term, it often just takes some rough math to identify areas or risk that need attention.